|

|

|

|

.

Brown Line:

North Side Main Line

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Legend:

Click on a station name to see that station's profile (where available) |

|

|

|

|

.

Brown Line:

North Side Main Line

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Legend:

Click on a station name to see that station's profile (where available) |

Service Notes:

History:

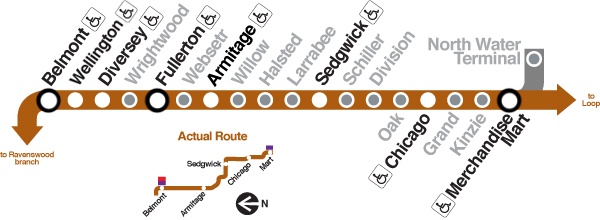

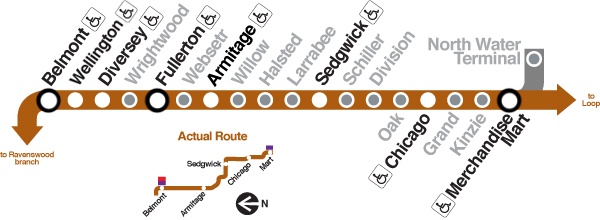

The southern half of today's Brown Line -- the portion between Belmont station and the Loop -- represents the trunk line of the old Northwestern Elevated and is often referred to as the North Side Main Line. At Belmont, the Ravenswood branch begins and the Brown Line veers off the North Side Main Line to follow it. The rest of the North Side Main Line -- the original 1900 line to Wilson, and the 1908 extension beyond -- is covered by the Howard line local service and the Purple Line express service.

Looking north at Willow Street in 1897 as the Northwestern main line is under construction. The State Street Subway portal is now just north of here. For a larger view, click here. (Photo from the Chicago Transit Authority Collection) |

The company completed right-of-way clearance in 1895 and began erecting the line in January 1896 near the future site of Fullerton station. The Northwestern Elevated's charter from the city had stipulated that the main line to Wilson had to be in operation by 1897, but slow construction and a poor economy precluded this. The company petitioned the city council to extend the deadline, which they did, to December 31, 1897. Just as this extension was granted, however, the national economy faced a downturn. A shortage of funds forced construction to be halted, although by this time steel elevated structure had been erected from Grace Street to Fullerton Avenue, footings were in place for some distance south of Fullerton, and construction was in progress on an upper deck for the Wells Street bridge. It took financier and Northwestern Elevated backer Charles Tyson Yerkes another year to raise enough capital to resume construction. By late 1897, the structure was completed from Halsted and North to Buena Avenue, next to Graceland Cemetery. However, with financial problems again setting in, the company again had to petition for an extension from the city. Ultimately, the city had to begrudgingly grant two extensions because of missed deadlines. On Christmas Day 1899, the last steel span was lifted into place. The line was far from complete, however. Only one track was completed between Wilson and Kinzie (just north of downtown) and work hadn't even started on any but a few stations.

On May 31, 1900, the Northwestern began regular revenue service between the Loop and Wilson. Only half of the line's stations were ready for service on opening day, but the rest were opened as they were completed. The line's typical station houses were designed by William Gibb and constructed entirely of brick with terra-cotta trim in a Classical Revival design with Italianate influences. The interiors featured plaster walls with extensive wood detailing in the door and window frames, ceiling moldings, and tongue-in groove chair rail paneling. The platforms had two peaked-roof canopies of steel supports with gently-curved brackets and intricate latticework, covered by a corrugated metal roofing, and railings which consisted of tubular frames and posts with panels of decorative, vaguely diamond-shaped metalwork inside.

This view looks east on June 12, 1900 at the S-curve at where the Northwestern moves from over Franklin to Wells for the approach to the Loop. The sharp 90-degree curves were eased and banked in the 1920s and now look quite different, although most of the original bents and stringers are still present. For a larger view, click here. (Photo from the Chicago Transit Authority Collection) |

To put things in perspective, the section south of Armitage station is exclusively part of the Brown Line (and the Purple Line Express during rush hours). Trains on this portion run as expresses did for the Northwestern, operating on the inside tracks (though this is due to the closure of all the local stations on this section just as much as any other reason). Between Armitage and Clark Junction, the old Northwestern main line is shared by the Red and Brown Lines. Here, Brown Line (and Purple Line) trains run as the locals did for the Northwestern on the outside tracks (Tracks 1 and 4) and make all stops. The Red Line operates on the inner tracks (Tracks 2 and 3), as Northwestern expresses did, and make limited stops. At Clark Junction, the Brown Line leaves the old North Side Main Line for the Ravenswood branch; the Red Line continues north on the inside tracks as the "local" and the Purple Line Express continues on the outside tracks as the "express".

However, one must recall that these operations are modern inventions of the CTA (see more on this below), and early operations were very different in both detail and concept. Early on, there were no through-routed services -- all trains terminated in the Loop -- and for the first seven years no Ravenswood branch at all. From 1900 to 1907, all trains that traversed the North Side Main Line went from the Loop to Wilson, with some running local and others running express. There was much tweaking of these operations as well. Originally, expresses stopped at Sheridan, Belmont, Fullerton, Halsted, Sedgwick, and Kinzie, but express stopping at Halsted and Sedgwick was short-lived, suspended in September 1900. Another concept that was used quite a bit back then (especially after the North Side Main extension north of Wilson opened in 1908) but is virtually unknown in Chicago now is the idea of "zone expresses". Zone express service offers express service, with few stops, in one portion of a route and then operates local service at the other end of the route. This provides a much more flexible service for riders by allowing those who live at local stops at the outer portion of the route to still enjoy the benefits of fast express service without changing trains, not to mention that it uses infrastructure more efficiently. Starting in 1902, some northbound afternoon expresses made local stops north of Fullerton to give passengers heading to these stations a faster trip. (This concept was more fully developed after 1908, when the extension opened. For more on this, see the Howard line history.) At some point, Chicago was added as an express stop as well.

Branches and Additions to the North Main

Clark Street junction and station as they looked just prior to the 1913 switch to right-hand running. A Loop-bound Ravenswood train waits at the far left for southbound express and local trains to pass. For a larger view, click here. (Photo from the CTA Collection) |

By 1907, the Loop had already reached capacity, requiring the other three "L" companies to reopen their original stub terminals at Congress, Market and Wells, which were closed when the Loop opened. Though the Northwestern Elevated, unlike the other three lines, always ran into the Loop, they too saw the wisdom of a terminal for rush hour overflow just outside the Loop. The city council approved a franchise July 17, 1908 and the Northwestern got the terminal built and opened in just four months! The North Water Terminal was located on a short branch off the North Side Main Line just north of the Chicago River. Just south of the Kinzie Avenue station, a two-track line branched off to the east over North Water Street (later renamed Carroll Avenue), little more than a glorified right-of-way in which the Chicago & North Western ran. The two-track branch stretched only two blocks to Clark Street and ended in a three-platform terminal: a side platform for each track, plus mutual access to a center island platform. No trains were run into North Water Terminal in the morning, nor on weekends, but in the evening rush express trains were dispatched from the North Water Terminal to the Evanston and Ravenswood branches.

About the same time, another two stations were added to the Northwestern main line: Oak and Willow. Both stations were included in a draft of the franchise to build the Ravenswood Branch in 1906 that was ultimately rejected, and although the Northwestern Elevated did not particularly want to build these stations (and indeed they had rather modest traffic after opening), one can assume that whether they were built as a mandate of the final franchise or not, they must have been constructed shortly thereafter.

Crosstown Service Inaugurated

A train of wood cars are northbound on the North Side Main Line passing Illinois Crossover circa 1920. Grand station is under construction in the background. For a larger view, click here. (Photo from CTA Collection) |

On the Near North Side, a series of infrastructure changes occurred during the period of a decade between the early 1920s and early 1930s. In 1920-21, the Wells Street bridge was rebuilt, with the old swing bridge replaced with the current bascule bridge. Both bridges had two decks -- one at street-level for vehicular traffic and one above for the "L". The old bridge was taken out of service on Friday, December 2, 1921, the new bridge lowered and trackwork completed, and the new bridge came into use the following Monday morning. Later in the 1920s, the Chicago Rapid Transit undertook work to ease the sharp S-curve at Hubbard Street that took the "L" from over Wells Street to over Franklin Street. Corner properties were acquired and the structure realigned so that the curves were softer and the tracks were slightly banked, allowing faster speeds through the S-curve, although trains still had to reduce speed.

After the Chicago & North Western moved from its terminal at Wells and Kinzie to Madison Street in 1911, the Kinzie station of the Northwestern Elevated saw a drop in traffic and was no longer situated in an optimal location. Although Kinzie station stuck around for several more years, it was later demolished and replaced by Grand station a few blocks north in 1921. Grand station served the entire Near North Side by the Chicago River for several years and was more ideally situated to serve the warehouses, manufacturing, and other uses seen in the surrounding area.

Crosstown service was revamped several times in the years that followed. On February 23, 1931, the Chicago Rapid Transit (CRT), who'd taken over operations from the CER, made a few changes to crosstown service. The Wilson-Englewood and Ravenswood-Kenwood through-routes were swopped. To better adjust to the traffic patterns, the Ravenswood-Englewood/Normal Park through-route was only in effect in rush hour; at all other times, Ravenswood trains terminated in the Loop. With the opening of the State Street Subway on October 17, 1943 the Loop's severe congestion could finally be relieved. Englewood/Normal Park-Ravenswood trains were rerouted to the new subway. Englewood and Ravenswood trains were through-routed at all times from then on, discontinuing the off-peak Ravenswood-Loop runs... For the time being... |

|

|

Ravenswood service on the North Side Main Line as it appeared circa 1960. The service pattern dated from the North-South reorganization of 1949. In 1970, Grand closed; In 1983, Diversey and Armitage changed from "B" and "A" stations, respectively, to "AB" stations. Otherwise, the pattern remained unchanged until skip-stop service was abandoned in 1995. (Graphic by Graham Garfield, based on CTA maps of the period) |

Developments in the CTA Era

The Ravenswood service as we know it today (now under the name "Brown Line") was formed after the Chicago Transit Authority took over operation of the rapid transit system in 1947, when the CTA began making a series of changes in quick succession.

In the mid-1950s, the North Main Line was an interesting mix of equipment: the CTA's newest, the 6000-series, and some of its oldest wood cars. Although the Ravenswood Line had a handful of 6000s assigned too, a good portion of service was still provided by half-century-old wood cars. A former-Met car is operating on a southbound Ravenswood "A" run on the left, while a Jackson Park "B" train led by a flat-door 6000-series car and a Howard "A" train trailed by a curved-door pair of 6000s pass on the inner express tracks at Armitage Interlocking on June 1, 1956. For a larger view, click here. (CTA Photo) |

The skip-stop system was tested with great success first on the Lake Street Line in 1948, and the North-South operations were chosen as the next section to be improved. By early 1949, service from the Ravenswood branch on the North Side Main Line consisted largely of Ravenswood-Englewood/Normal Park express trains that operated via subway. In addition, there were a few Ravenswood-Loop express trips in the Monday-Friday morning rush hours and a few northbound North Water Terminal-Ravenswood trips in the Monday-Friday evening rush. These routings, combined with the other litany of diverse North-South services, were thus highly complex and any change to the schedule would cascade through the system and cause numerous problems. As such, it was decided to greatly streamline the crosstown services into just three simple routes.

Effective August 1, 1949, the Ravenswood Line, as it was to be known in the modern era, was instituted. During normal service hours, trains operated from Kimball to the Loop, moving from the subway back onto the Loop Elevated at all times. During owl hours, trains were truncated back to a shuttle service, operating from Kimball to Armitage, with transfers to the newly created North-South Route (Howard-Englewood-Jackson Park line) at Fullerton. At the same time, A/B skip-stop service was instituted on the new Ravenswood Line on weekdays and Saturdays from 6am to 9pm. Under the skip-stop system, Wellington, Armitage, and Grand on the main line became "A" stations, Diversey and Sedgwick became "B" stations, the rest being "AB" stations. Due to close spacing and poor patronage, many local stations were closed along the main line as well. These included Wrightwood, Webster, Halsted, Larrabee & Ogden, Schiller, Division, and Oak. Willow station had already closed several years before as a result of the construction of the State Street Subway. Additionally, the CTA closed the North Water Terminal and sent all Ravenswood trains around the Loop. The terminal was not, however, demolished immediately, retained for specials, charters, equipment storage, and emergencies. The faster service provided by A/B operations was welcomed, but had to be tweaked within a few years. Outside of rush hours, the frequency of Ravenswood trains was less than on the companion North-South Route, and the public perceived the intervals between trains as excessively long at those times at the "A" and "B" stations. So on January 6, 1952, the hours of A/B skip-stop service were cut back to Monday-Friday rush hours only, with local stops at all other times.

Changes continued to affect the Ravenswood services on the North Side Main Line for several years. With the elimination of separate express and local services in 1949, compounded by the rerouting of a majority of trains into the State Street Subway since 1943, the four-track main line between Chicago and Armitage provided far more capacity than was actually needed for the servicing being run. To be sure, this section of track was still a busy place during rush hour when a busy combination of Ravenswoods and Evanston Expresses plied the same right-of-way as North Shore Line interurbans, but in the off-peak it was rather more calm. This began a period in which two of the four tracks on this two mile section were brought in and out of service. On January 2, 1951, tracks 2 and 3 (those used today for Brown Line service) was used for lay-ups midday just north of Chicago station, with Ravenswood and North Shore Line trains consigned to Tracks 1 and 4 on the outside. This was a short-lived practice, however, lasting only until February 13. With limited use of the two of the four tracks between Chicago and Armitage, the hours of manned operation for Chicago Tower, which controlled access where the two-track line fanned out to four tracks, was cut to weekday rush hours in April 1954.

By the mid-1950s, 6000-series cars were providing the majority of service on both the Ravenswood and North-South routes, making the North Side Main Line an ideal spot for PCC car fans. South of Armitage, where the State Street Subway joins the elevated, Ravenswood trains pass on the outside tracks as a northbound Howard "A" train emerges from the incline. Note that the Howard train has a "Baseball Today" sign on its front chains and that the Rave trains are using the outside tracks south of the incline, which are out of service today. For a larger view, click here. (Photo from the CTA Collection) |

During the 1950s, one aspect that seemed to change with regularity was the assignment of rolling stock to Ravenswood service. Up to 1949, Ravenswood-Englewood trains were all made up of 4000-series equipment due to the prohibition against wood cars in the subway. When the Ravenswood Line was made independent of other North-South services in August 1949, all of the steel 4000s were reassigned to the new North-South Route via the subway and the Rave was given a fleet made up entirely of old wood-bodied equipment, much of it on its last legs. But the equipment did a 180-degree turn in spring 1951, when enough of the CTA's new flat-door 6000-series PCC cars were assigned to the line to provide all base service; only owl service continued to be provided by wood-steel cars. By June 1954, enough 6000-series cars had been assigned to Ravenswood to allow all service to be provided with the new cars, largely eliminating the wood cars from the route. A few remained as late as 1957, however it's questionable how much service they actually saw. In June of '57, over a 100 4000-series "Baldies" were assigned to Ravenswood, allowing the last of the wood cars to be removed from service. About the same time, the number of 6000s on the route was reduced, but over 30 remained, supplemented by the four orphan 5000-series prototype cars on October 7. The 5000-series articulated cars usually trailed four 6000-series cars in Ravenswood tripper service, but there was a period when two six-car trippers of 5000-6000-5000 format operated. In any case, trains using 5000s were marshaled so as to avoid the conductor's location being in the 5000 as the conductor could not examine the side of his train from a 5000 after the doors were closed. The 5000s remained on Ravenswood until being transferred to their final home, the Skokie Swift, in 1965.

Car assignments on the Ravenswood continued to fluctuate for several years. In 1960s, the CTA's eight high-performance PCC test cars -- 6000-series cars 6127-6130 and 1-50 series 1-4 -- were put in regular-speed service on the Ravenswood route in their distinctive maroon and silver gray color scheme. Their presence was short-lived, with cars 1-4 reassigned in 1964 and by '67 only cars 6127-28 of the high-performance 6000s remained, which were finally reassigned in 1971. Although some flat-door 6000s were always assigned to the route during this period, the majority of service was provided by 4000-series cars -- Baldies until about 1964-65, and plushies thereafter -- until 1971. In January, half of the 1-50 series fleet and some additional 6000s were assigned to the route, with enough PCC cars assigned by April 1971 to provide all base service. In September, the last 4000s were removed from the route. For the next decade or so, the branch was populated entirely by the St. Louis PCC equipment, with a collection of later-model 6000s joining the route in the mid-1970s.

The Rave Hits Troubled Times

The 1960s saw a continued erosion of Ravenswood service levels, especially between Armitage and the Loop, where ridership was light and there were many paralleling rapid transit and surface lines. With less service on the North Main south of Armitage, Chicago Tower was removed from service in Summer 1961. Later that year, effective October 29, owl and Sunday service was cut back even further north on the North Side Main, with trains running only as far as Belmont. There, riders could transfer to North-South services. This, in essence, limited Ravenswoods service to the branch itself, running on the North Main only far enough to reach the first opportunity to transfer riders to a parallel service. This removed service from two more local stations, Wellington and Diversey, as well. Owl headways were also increased from 30 to 45 minutes at the same time.

A three-car train of North Shore Line Silverliners, led by car 251, the only Silverliner combine, is heading north near Webster in 1962. The interurban used the North Side "L" to enter downtown Chicago beginning in 1919; in less than a year, it would abandon service. For a larger view, click here. (Photo by Jim Northcutt from the IRM Collection, courtesy of Peter Vesic) |

However, it was in the 1970s and '80s that the Ravenswood portion of the North Side Main Line, as with many lines, saw a steady reduction in service and closure of stations and entrances as the CTA's financial problems reached critical mass -- mirroring transit authorities and government agencies across the country -- the agency needed quick and drastic ways to reduce costs. The year 1973, which saw an extensive series of closures and cutbacks across all lines, was particularly bad. First, Sedgwick station, which had moderate ridership, closed in January. Unfortunately, this created a two mile gap in stations on the Ravenswood Line and left a sizable number of people without "L" service (although there was bus service to the area). In February, the CTA reduced agent coverage at several branch stations, particularly in the evening and on weekends. But, in April, Sedgwick station was reopened due to political and community pressure.

It was also during this period that the outside, former local tracks between Armitage and Chicago -- Tracks 1 and 4 -- were finally taken out of service and abandoned. As early as the early 1950s, with North-South crosstown service diverted off the North Main and into the State Subway, use of the four-track capacity had declined. Abandonment of the North Shore Line interurban, which used these tracks to enter the Loop, in January 1963 further decreased the need for such capacity. By this point, "L" trains used Tracks 2 and 3 at all times, though 1 and 4 were kept in serviceable condition. Over the following decade, service switched back and forth between Tracks 2 and 3 (the inside, former express tracks) and 1 and 4 as trackwork was done to 2 and 3. As Sedgwick was the only station left on this stretch between Armitage and Chicago, and it had been designed over 75 years before as a local/express station with dual island platforms serving all four tracks, the CTA's ability to provide service to Sedgwick was not impaired by switching Ravenswood service between the various tracks. But, with the Authority's maintenance and operating funds declining, and no real need for all four tracks anyway, Tracks 1 and 4 were removed from service for good on October 18, 1976. A few weeks later, on November 4, sidings were put in service on Track 1 just south of Armitage and on Track 4 just north of Chicago, each of which can hold about 16 cars, for short-term equipment storage and emergency lay-ups.

By the 1980s, a lack of funds and maintenance resulted in two of the four tracks south of Armitage being abandoned and left to deteriorate while weeds and trees overgrew along the right-of-way, giving an unkempt appearance. In this September 1989 view looking south at Schiller Street., a northbound Ravenswood All-Stop train led by a 2600-series car has passed the Oscar Meyer plant in the background. Today, this view looks very different. For a larger view, click here. (Photo from the Graham Garfield Collection) |

In the late 1970s, the Ravenswood again continued the mantle of a line of patchwork equipment assignments. The 6000-series assignments stabilized with service provided by the same flat-door 6000s that started out on the route, supplanted with "red-tagged" 6400-series units relegated to "belly car" service due to their lack of cab signals. Still, not all cars were hand-me-downs. As new, modern cars were bought by the CTA a few were assigned to the Rave so that at least some of the assigned fleet was new and modern. The 1-50s were removed from the route, with the first 34 cars of the new 2400-series assigned to replace them. By 1985, enough 2600-series cars had been delivered from Budd/Transit America that the 2400s were removed from the route and assigned entirely to West-South service, with more 2600s to Ravenswood to supplement the 6000s. In Summer 1987, more 2600s were delivered and more 6000s were retired from the system, leaving the last of the 1950s PCC cars operating on the Ravenswood Line. A collection of 6000s and 2600s provided service for the next several years.

Unfortunately, not all of the changes in the late 1970s and 1980s were as positive. The broadest service cut on the Ravenswood came in September 1976 when all owl (late night) service was eliminated on the entire route. In 1981, Monday through Saturday late evening Ravenswood service was truncated back on the North Side Main Line from the Loop to Belmont station, where riders could transfer to North-South trains. At that point, late night service was truly relegated only to the Ravenswood branch itself, with transfers to other rail service made at the first opportunity. By the early 1980s, there was some discussion of abandoning Ravenswood service altogether, although the Loop to Belmont portion, with its parallel "L" and bus services, was the most likely target. In the meantime, as headways were spread A/B skip-stop service was slowly eroded. In June 1983, Diversey, and Armitage -- "B" and "A" stations, respectively -- were made "AB" stations, reducing the speed of service and increasing the number of local stops.

Luckily, the late 1980s and 1990s brought new changes to the Ravenswood, ending some eras in the branch's life but beginning new chapters in other ways. In 1987-88, the original 1930 Merchandise Mart platforms were replaced with a modern white steel and glass station of the "open plan" design, characteristic of new "L" construction. A few years later, the fare control area was also renovated.

One end that came on the Rave represented a systemwide closure of an era: On December 14, 1992, the last 6000-series train made its regular in-service run on the Ravenswood. At the end of the day, the 6000-series cars were removed from passenger service, and while many remained in work service and several of their 1-50 series PCC brethren remained in use on the Evanston and Skokie lines for a year or so, the retirement of these cars represented the end of the road for a series of cars many generations of Chicagoans had come to know as the typical "L" car.

However, a new set of changes, representing a bright future for the Ravenswood, were on the horizon...

Ravenswood Goes Brown, Ridership Explodes

Effective February 21, 1993, the Ravenswood Line (including the branch) was officially renamed the Brown Line as part of the CTA's adoption of color-coded names for its routes -- to make the system friendlier to new or tourist riders, some of the names were deemed too cumbersome -- though the old name lives on with many riders and CTA employees. Some cars began carrying the new color-coded roller curtains -- now representing line color, not stopping pattern -- as early as Fall 1992, though the changeover was not completed for several months after.

In the early 1990s, the Brown Line had all of its rolling stock replaced with new 3200-series equipment. Here, car 3434 brings up the rear of an inbound Brown Line train near Hill Street, looking southwest on April 18, 2003. The CTA had begun to remove the unused outer tracks around Church Curve, replacing them with fiberglass catwalks. For a larger view, click here. (Photo by Graham Garfield) |

Some minor structure work was undertaken in 1994. The four-track elevated structure in the vicinity of Division Street (of which the outside tracks have been out of service for several decades) was reduced to two tracks in a project that saw the replacement of 15 spans under the two inner tracks and the removal of the extraneous steel. The work began on November 10, 1994 and was half over by the end of the year. It was completed in early 1995. The fact that, at the time, no Brown Line (or Purple Line Express) service operated over this portion of the line on Sundays helped accommodate the work.

Around this time, the Brown Line experienced something else it (and several other lines) hadn't seen in a long time: increasing ridership. As ridership on the rest of the system continued its downward spiral, traffic on the Ravenswood Line increased by 30% -- from 8.1 million passengers a year to 10.6 million -- between 1987 and 1998. In the late 1990s, when systemwide "L" ridership figures began an upswing for the first time in decades, the Brown Line was responsible for a large part of it. The rebound was the result of the neighborhoods along the line -- the Near North, Lincoln Park, and Lakeview on the main line and North Center, Ravenswood, Lincoln Square, and Albany Park on the branch, among others -- rebounding in population and, more importantly, popularity. Lincoln Park, perhaps the most famous and certainly the most posh, is a telling example. Once a racially and economically diverse area, by the 1990 census the neighborhood was 85% white. Many Hispanic and African-American families who once lived there left, pushed out by what some call revitalization, but what others less positively call gentrification. In 1990, 7 in 10 Lincoln Park residents were under 40 and the median household income was $41,016. With the restoration of rundown vintage homes, real estate prices soared. Some houses sell for upwards of $1 million. Many of Lincoln Park's 61,000 residents live in high-rent apartments. Lincoln Park's population, according to the 2000 census, increased 5.3% from 1990 and 5.1% from 1980. Lincoln Park's example is perhaps more radical than the other neighborhoods, but not atypical.

Car 3308 leads a southbound Brown Line train pulling into Armitage station on December 28, 2001 as a Red Line train passes on track 2, looking north from Armitage Tower. For a larger view, click here. (Photo by Graham Garfield) |

In Summer 2000, the CTA restored more Brown Line service as a result of increasing ridership. Effective July 16, 2000, the CTA restored weekend service to the Loop until midnight on the Brown Line, a move that CTA officials said would pay for itself because of strong gains in ridership. Before the change, the Brown Line operated between the Loop and Kimball on Saturdays from 5:45am to 8pm only, while on Sundays, there was no service south of Belmont. Afterward, service to the Loop began at 5am and stretched to 11:50 p.m. on Saturdays, Sundays and holidays. The improvement allowed for better connections with other CTA lines in the Loop and brought service to six stations north of the Loop that were closed when Brown Line trains stopped running south of Belmont after 8pm on weekends and holidays.

In 2002, the "L" span over Wacker Drive was rebuilt as part of the reconstruction of the double-deck riverside drive. The new bridge was built next to the old structure, then over the course of one weekend the old structure was demolished and the new moved into place. Looking southeast from the CTA's Merchandise Mart offices, a northbound Brown Line train passes as the new bridge span nears completion. For a larger view, click here. (Photo by Jeff Sriver) |

Increased population along the Brown Line has translated into increased ridership. According to the 2000 Census, the number of commuters in Lincoln Park who took public transit (or a taxi) to work was 41.5% and 33.7% took it on the Near North Side, with public transit representing the dominant transportation mode for commuting in those neighborhoods. By 2001, the Brown Line carried approximately 104,000 riders on an average weekday. Ridership on the Brown Line increased by another 24% between 1997 and 2000. Now, the line's ridership has passed the 13 million per year mark and continues to rise.

Brown Line Capacity Expansion Project

As a result of the increasing ridership, during peak hour periods the CTA was transporting crush-loads of customers on every car of the Brown Line by the early 2000s. Crush-loads throughout peak travel times meant sometimes trains were forced to leave commuters standing on platforms to wait, sometimes for one or two trains to pass them by before they were physically able to board a train to continue their trip at the stations close to the Loop. All Brown Line stations were only able to accommodate six-car trains -- with the exception of Merchandise Mart, Chicago, Fullerton and Belmont, which could hold eight-car trains -- but the Brown Line was one of only three CTA rail lines that could not accommodate eight-car trains (the other two are the Purple and Yellow lines). Since the mid-1990s, CTA had made additional operational changes to accommodate demand on the Brown Line, including having Purple Line trains stop at Brown Line stations from Belmont to downtown Chicago. Despite these service adjustments, persistent crowding on Brown Line station platforms negatively affected the rail transit experience for passengers throughout the corridor.

Because of the resurgence of popularity of many of the neighborhoods along the Brown Line, rush hour trains are standing room only. Some are crush-loaded, forcing trains to leave commuters standing on platforms to wait for another train. By the time of this view on the morning of April 25, 2003, rush hour was beginning to wane, but the passengers of car 2998 still had to stand in the aisles. For a larger view, click here. (Photo by Graham Garfield) |

By far, the largest part of the Brown Line Capacity Expansion Project was station reconstructions. Of the Brown Line's 19 stations, only one (Merchandise Mart) was not touched at all due to its modern construction (1988) and ability to berth eight-car trains. Another two (Kimball and Western) only received small platform extensions and other modest work. The other 16 stations were completely or largely reconstructed. The goal of the rehabilitation of the Brown Line stations is to alleviate crowding, increase ridership capacity, improve passenger flow and make each station ADA compliant. At the same time, some additional renovation work was undertaken. Five new traction power substations were constructed, equipment at two remaining substations was upgraded and two substations were retired to provide the additional power needed to run eight-car trains. The train control system was upgraded/replaced, providing bi-directional signaling and renewed grade crossing signal protection on the ground-level portion of the line. A new fiber optic communication system was provided between all of the stations and the CTA Control Center.

While few deny the benefits of running longer trains with more capacity -- especially the commuters who cram into those trains every day -- some members of the public were worried about the side effects of the project. Nearly 100 private parcels of land -- homes, restaurants, taverns and at least one church property -- stood in the way of the CTA's $540 million renovation of the Brown Line. For some, it was parts of backyards or entire homes or apartment buildings that were acquired, while for others it was businesses that were taken. The expanded platforms -- both longer for 8-car trains and wider for ADA compliance -- accounted for most of the air rights to be purchased from land owners. The elevators added at 16 stations also took up some of the private property.

For preservationists, however, the arguments were somewhat different, though no less impassioned. The Landmarks Preservation Council of Illinois felt that the renovation might leave few of the quirky historical details that add to the character of the line. The CTA pointed out that it worked with state and federal preservation agencies on plans for the rehab. In the end, there were several preservation victories in the Brown Line designs along with some preservation loses.

On April 13, 2004, the CTA announced that it had officially received a Full Funding Grant Agreement (FFGA) from the Federal Transit Administration (FTA). Mayor Richard M. Daley, CTA President Frank Kruesi, Senator Richard Durbin, Congressman Rahm Emanuel, Governor Rod Blagojevich, and other officials announced the agreement allowing the Authority's project to rehabilitate 18 stations and expand capacity of the Brown Line to proceed at Ann Sather's Restaurant near the Belmont station.

Construction for the Brown Line Capacity Expansion Project was scheduled to begin in 2004, taking place on weekdays, evenings and weekends but with no station closures to complete projects as quickly but with as little disruption as possible. However, when the Brown Line project was advertised and bids for the construction portion were opened on May 5, 2004, the two responses that were submitted both exceeded the CTA's construction budget. The CTA had previously reported publicly that its total project budget, including items such as insurance, design, engineering and property acquisition, as well as construction, was $530 million. The bids the CTA received for the construction portion of the project were for $420.5 million and $541.2 million.

On June 9, 2004, the Chicago Transit Board voted to repackage and rebid construction work for the Brown Line Capacity Expansion Project. The CTA said the re-advertisement would not affect the project deadline, as the repackaging would allow for flexibility in the way work is scheduled. The project was reorganized into several discrete pieces to help attract more competitive construction bids. Signal system upgrades and electrical substation work formed one package. Work on station renovations were grouped into five separate packages according to location. The first package expected to go out for bid was Belmont/Fullerton. The other four packages were Armitage/Sedgwick/Chicago, Kimball/Kedzie/Francisco/Rockwell/Western, Damen/Montrose/Irving Park/Addison and Paulina/Southport/Wellington/Diversey.

At its monthly meeting on October 14, 2004, the Chicago Transit Board approved a $45.5 million construction contract for Aldridge - Mass, AJV (A Joint Venture) to upgrade the signal system. The state of the art signal system provided the CTA and its customers greater service reliability and enhanced flexibility in service scheduling. Aldridge rehabilitated the Brown Line's signal system from Kimball to Western, which involved installing signal equipment along the tracks, installing six new crossing gates and circuitry where the Brown Line crosses at street level at Spaulding, Kedzie, Albany, Sacramento, Francisco and Rockwell, and rehabilitating Kimball Tower from where signals control switches and direct trains. At Clark Junction, the location where Brown, Purple and Red Line tracks merge on the city's North Side just north of the Belmont station, the contractor installed a new signal system from Armitage to Addison, providing signals for 14 rail crossovers, and rehabilitated Clark Tower located at the junction. Work began in fall 2004. Work at Clark Junction concluded in late 2006 and signal and grade crossing work between Kimball and Western wrapped up by summer 2007.

The station packages proved to be a bit trickier. In addition to the efficiencies hoped to be gained by bidding the stations as separate, grouped packages, $152 million worth of cost savings needed to be identified. The CTA reexamined their station designs and made many modifications, including the retention and refurbishment of many components, such as platform canopies, that were originally going to be completely replaced. Overall, the CTA focused largely on non-customer components such as communication rooms and janitor closets to further reduce the overall cost of construction. But another $22 million in construction costs still needed to be saved. This forced a difficult decision on the part of the CTA: to go back on their promise to keep stations open during construction and propose temporary closures to allow work to proceed more quickly and give contractors the efficiency and economies of unobstructed access to the site.

Despite strong objections from many citizens and elected officials, the CTA announced on Friday, January 28, 2005 that in order to stay within the project budget and preserve amenities planned for neighborhood stations, the CTA would implement temporary closures of some Brown Line stations during construction. Under the plan, three stations -- Fullerton, Belmont and Western -- remained open throughout construction. Maintaining service at these three heavily trafficked stations for the duration would minimize the effect of surrounding temporary station closures.

Armitage, Sedgwick and Chicago remained open on weekdays. It was, however, necessary to concurrently close all three of these southernmost Brown Line stations for up to six weekends during the construction period to allow construction crews unlimited access to station platforms. During these periods, customers were encouraged to use the most convenient existing CTA bus and rail service in the area.

Damen, Montrose, Irving Park, Addison, Paulina, Southport, Wellington and Diversey were subject to temporary weekday and weekend closures, with no adjacent stations being closed at the same time. Customers were encouraged to use the next-closest or most conveniently located station during any given temporary closure.

Kimball, Kedzie, Francisco and Rockwell were subject to two types of temporary closures. On weekdays and weekends, these stations experienced temporary closures, with no adjacent stations being closed at the same time. In addition, under the plan, CTA could concurrently close all four of these northernmost Brown Line stations for up to 10 weekends throughout the construction period to allow construction crews unlimited access to station platforms. During these periods, customers were encouraged to use nearby existing CTA bus service.

The Brown Line station closings began after September 2005. The closings were aimed at minimizing the time to rebuild stations to make them accessible, lengthen platforms to accommodate longer trains, complete track work and modernize rail signals.

While many members of the public and elected officials said they understood the conundrum and would choose closures over lost amenities if forced into that choice, many were still critical of the decision, especially given the CTA's original promise to keep the stations open. Chairman Brown said that after an independent review, she decided that the temporary closings are necessary to stay within the project's $530 million budget and retain design amenities that include escalators, platform canopies and bicycle racks and said the "long-term benefits far outweigh the short-term inconvenience." Still, in a letter to the Federal Transit Administration outlining changes in the federally funded project's plan, Brown wrote: "CTA should have never promised such unaffordable station designs, and it should never have pledged to keep stations open."

Starting Monday, April 2, 2007 Red, Brown and Purple Express trains began operating on three tracks instead of four at the Belmont and Fullerton stations to allow one of the four tracks along the platforms at each station to be taken out of service while the platform is rebuilt and tracks are reconfigured to allow room for elevators to be installed. When Three-Track Operations began, Track 3 was removed from service at Fullerton (a new Track 4 having already been placed in service) and Track 4 was removed from service at Belmont. However, the specific track to be taken out of service varied during the course of the project.

The reduction from four tracks to three had a profound impact upon the peak of the morning and afternoon weekday rush period, limiting capacity and reducing the number of trains the CTA could run through the corridor. CTA encouraged customers to consider adjusting their travel patterns -- switching to bus service, leaving earlier or later, or making a connection that would help speed their trips. To help support the additional demand that was expected to be placed on the bus system, CTA boosted bus service at those points where rail customers were expected to migrate.

Although fewer trains operated, CTA staged additional Brown Line trains that travelled only along the heaviest used portion of the rail route during rush hour, turning from north back south at Lakewood-Seminary Interlocking south of Southport station, in order to provide some room for customers who board at stations closer to the Loop. In addition, rail service on the Blue Line, which is a convenient option for many, was supplemented by adding service along the heaviest traveled portion of that route during rush hour, with some trains turning back at Jefferson Park and UIC-Halsted during the morning rush period. Finally, Purple Line Express trains were rerouted to operate on the Outer track in the Loop -- the same side used by the Brown Line -- to make it easier for customers to board either route and exit the Loop at the first opportunity.

On Sunday, March 30, 2008, the next phase of three-track operation began. Southbound trains were limited to one southbound track at the Belmont and Fullerton stations. To help ease the impact, the CTA began operating eight-car trains on the Brown Line during morning and evening rush hours. The ultimate goal of the project, the introduction of eight-car service occurred nearly 18 months earlier than originally planned.

CTA President Huberman said that during peak morning rush period there would be four fewer Red Line trains traveling inbound from Howard to Downtown (from 19 to 15) but that additional southbound trains would be staged south of Fullerton for use as needed. Four fewer Brown Line trains (16 to 12) would operate during the peak, however, due to the longer trains, capacity on the Brown Line woild be the same as it is was before phase three began. Purple Line Express service levels remained the same (4 trains).

In order to provide eight-car trains, Paulina and Wellington stations, the last unrehabbed staions with six-car platforms, closed for renovation on March 30.Also on March 30, the CTA reopened the Southport station and opened a temporary station at Diversey. Using a temporary station at Diversey made it possible to reopen for service nearly three months earlier than originally planned. Work to install elevators and complete the stationhouse at Diversey continued throughout spring 2008.

In May 2008, the CTA committed to restoring normal four-track operation six months earlier than originally planned by accelerating the construction work to realign the tracks at Belmont and Fullerton.

Three-track operations began to wrap up in late 2008. On Saturday, November 22, 2008, construction was completed on the new Track 1 at Fullerton, with the new Track 1 and the remainder of the new southbound platform opening for service. With this change, service was available on both southbound tracks, signaling the end of Three-track operation during rush hour at Fullerton. The service constraint continued at Belmont for another month, however, through December 20, 2008. On December 19, CTA President Ron Huberman was joined by 47th Ward Alderman Gene Schulter officially commemorate tthe return of four-track operation at a ceremony at the Damen Brown Line station, which was also reopening.

The project's Full Funding Grant Agreement with the federal government required that the CTA complete the project by the end of 2009. Separately, there was a 2008 deadline for accessibility work planned for the Fullerton station. Both deadlines were met.

Only two years after the completion of the Brown Line Capacity Expansion Project, the wooden decking used at many stations began to deteriorate. Early evidence of the problem occurred at Francisco station, one of the first stations rebuilt in the project (making the planks there about six years old at the time the deterioration became noticeable). As of the end of August 2011, the CTA had spent $350,000 to replace and weather seal new boards in a spot-replacement fashion at 14 stations, but the agency estimated it would have to spend about $175,000 more to completely replace the Francisco platform starting in September 2011.1 By the end of 2012, the total cost of replacing the wood decking at all of the affected Brown Line stations was $5.7 million.2

The problem occurred because the CTA changed materials for the project from the creosote-treated wood it had historically used to a wood product that included required fireproofing. The wood the contractors used included a fireproofing chemical on the wood that the CTA mistakenly believed would protect it against the elements as well.3

"The materials that were originally installed had a much shorter lifespan than they should have," said CTA spokesman Brian Steele. "They only lasted about five to six years. The materials that were installed, in moving forward, will have an expected lifespan of 15 to 20 years, and that's really what should be expected," Steele said. Asked by CBS Chicago whether the people responsible were held accountable, Steele said, "The staff that worked on that project are no longer with CTA. ... They've moved on to other employment. They retired."4

Thirteen stations total had their wood decking completely replaced, with the Diversey station the final Brown Line stop to have its platform replaced.5

Wells Street Bridge, Hubbard Curve Rehabilitation

The Chicago Department of Transportation (CDOT) performed a year-long reconstruction of the historic Wells Street Bridge in 2012-13, during which the CTA took the opportunity to perform track renewal at Tower 18 and on the Brown Line from the Loop through Hubbard Curve north of Merchandise Mart station.

The bridge's historic elements, railings, bridge houses and major structural components were replaced to preserve the 1920s look of the bridge. Crews replaced the trusses and all of the steel framing for the lower level road and upper level railway structures. The mechanical and electrical components were also replaced. The bridge contractor, Walsh/II in One (JV), began work on November 5, 2012, and was expected to be complete by the end of November 2013. Southbound vehicular and pedestrian traffic on Wells was rerouted, including the #11 and #125 buses.

While the roadway was closed for the duration of the project, the construction work was designed to keep CTA rail service interruptions at a minimum. "L" trains continued to use the bridge during the project, except for two nine-day service interruptions in Spring 2013, when the CTA rebuilt the Tower 18 Loop 'L' junction at Lake and Wells streets. That work required two nine-day closures of the Wells bridge to Brown and Purple line trains, one in early March 2013, the other in late April.

The Tower 18 work was originally scheduled to be part of the Loop Track Renewal project, which was undertaken between April and November 2012. But by performing the work while CDOT completes the Wells Street Bridge repairs, CTA reduced the duration of the work by eight days. Additionally, combining the work saved CDOT and CTA $500,000 in construction coordination cost.

During the two nine-day closures, which ran from early morning Saturday through early Monday of the following week, alternative bus and rail service was provided. On weekdays, Brown Line trains alternated between terminating at Merchandise Mart station or continuing into Downtown through the State Street Subway. Bus shuttles were available from the Mart as well as special shuttle service on the Loop Elevated.

Ravenswood Connector Rehabilitation Project

The CTA undertook two projects during the 2010s to rehabilitate the elevated structure, tracks and signal system on the Brown Line between the Merchandise Mart and Armitage -- a section referred to colloquially as the Ravenswood Connector -- to improve train speeds, providing expanded capacity on the line to reduce crowding, add more frequent service, and deliver safer, more reliable service. Collectively branded the Ravenswood Connector Rehabilitation Project, the program actually consisted of two separate projects -- a structure and track renewal project, and a complementary signal renewal project that built on the earlier initiative's improvements.

Ravenswood Connector Track Renewal

The $90 million Ravenswood Connector track renewal project was designed to eliminate more than 70 percent of the slow zones -- two miles worth, where speeds were restricted as low as 15mph -- that existed on the Brown Line at the start of the project.

The project was announced on October 9, 2012, after the CTA and City reached a new labor agreement with the International Association of Bridge, Structural, Ornamental and Reinforcing Iron Workers Local Union #1, who covered nearly 70 ironworkers at the CTA. The new agreement provided more flexibility and cost savings for CTA construction work, with changes that allowed the CTA to hire additional iron workers to repair and maintain the system's aging infrastructure more efficiently. Local #1 Iron Workers handled much of the structural ironwork repairs on the Ravenswood Connector, representing more than half the project, including repair and replacement of components on the steel structure.

Beginning Sunday, September 8, 2013, CTA ironworkers initiated major project work following months of preliminary preparation on the Connector project. The first phase of work included the repair and replacement of components on the steel structure between the Merchandise Mart and Armitage stations. The preliminary project work began in summer 2013 with crews taking measurements and fabricating replacement infrastructure components. Beginning in fall 2013, CTA crews renewed key elements on the more than 100-year-old structure by replacing flange angles, which are critical brackets that strengthen the elevated structure and support the tracks. CTA in-house forces also made some track repairs, working on rail tie replacement for immediate train-speed improvements south of Armitage.

To minimize the impact to service, structural repair work was performed mostly late at night and on weekends. During these times, trains traveling in both directions operated on a single track through the work area.

Once a significant amount of the structural work was completed, the CTA began replacing deteriorated rail ties and track components. The CTA awarded a $40.3 million contract to Kiewit Infrastructure Co. on August 13, 2014 for this second phase of the project. Kiewit crews began work in spring 2015, and replaced deteriorated rail ties, and replaced and repaired track components along the two-mile stretch.

To accommodate the track replacement work in the most efficient, economical way possible, the work was performed over a series of 15 weekends during which "L" service was suspended between Armitage and the Mart to give construction crews unobstructed access to the tracks and right-of-way. During these weekends -- of which the first was April 10-13 and the last was September 25-28 -- Brown Line trains were rerouted into the State Street Subway between 8pm Friday and 4am the following Monday. During these weekends:

The track renewal project was substantially completed during fall 2015.

Ravenswood Connector Signal Project

On September 9, 2015, the Chicago Transit Board approved a contract to begin design work on the Ravenswood Connector Signal Project. The project will replace the 40-year-old signal system on tracks serving the Brown and Purple Line Express between Armitage and Merchandise Mart stations. The modern signal system will enhance CTA's ability to move trains more efficiently and safely.

The Ravenswood Connector Signal Project replaced a signal system installed in 1975 that was out of date, contributing to congestion issues that developed from stronger-than-expected ridership growth on the Brown Line since the 2000s. The new signal system not only replaced aged equipment, but also relaid out the signal blocks for 8-car trains (rather than for 6-car trains, as the previous system had been), increased reliability through the use of more modern equipment, and optimized curve speeds, all of which potentially increased capacity on the line.

The $32.6 million contract was awarded to Ragnar Benson Construction LLC, following a Request for Proposals process. The contractor began design work for the signal project in fall 2015.

Customer impacts during the project were minimal, with much of the work occurring during off-peak hours.

The project was substantially completed in April 2018, with remaining "punchlist" work completed by the end of 2018.

|

cta6000s11.jpg

(74k) |

|

cta5001d.jpg

(94k) |

|

cta6056.jpg

(88k) |

|

cta6000s_4000s.jpg

(50k) |

|

ROW@Wellington01.jpg

(111k) |

|

cta4410b.jpg

(147k) |

|

cta4454b.jpg

(115k) |

|

cta6114.jpg

(106k) |

|

cta2001-2002a (167k) An 8-car train of 2000-series cars approaches Wellington while heading northbound on the North-South Route in July 1982. By this time, the 2000s were in platinum mist/silver and charcoal, and some were being repainted with red, white and blue ends and belt rails to emulate the then-new Spirit of Chicago paint scheme. But in the early 1980s, CTA restored the first set of 2000s, cars 2001-2002 seen here leading the train, to its original mint green and alpine white color scheme. Unfortunately, graffiti took it's toll on them and they were repainted into then-standard 2000-variant Spirit of Chicago paint scheme some years later. (Photo by Lou Gerard) |

|

cta2172-2171.jpg (209k) Car 2172 leads an inbound Evanston Express train, followed by its mate, 2171, passing over Wacker Drive in 1990. This view provides a good side view of the Spirit of Chicago livery, as it was adapted to the 2000-series cars. Note the M.A.N. articulated bus under the train on Wacker, operating on a downtown express route. (Photo by Lou Gerard) |

|

cta1892-1992c.jpg (256k) Commemorative "L" centennial cars 1892-1992 lead a southbound Evanston Express train crossing over Illinois Street on the Ravenswood-Loop Connector in September 1992. For the 100th anniversary of the first "L" line, a 2000-series pair was renumbered and repainted in an adaptation of the original South Side Rapid Transit livery. (Photo by Lou Gerard) |

|

cta2000s06.jpg

(35k) |

|

cta2600s01.jpg

(56k) |

|

cta2600s05.jpg

(39k) |

|

armitage02.jpg

(236k) |

|

ROW@Division01.jpg

(169k) |

|

ROW@ChurchCurve01.jpg

(163k) |

|

ROW@ChurchCurve02.jpg

(200k) |

|

ROW@Chicago01.jpg

(211k) |

|

ROW@Evergreen01.jpg

(149k) |

|

ROW@Armitage02.jpg

(166k) |

|

ROW@North01.jpg

(156k) |

|

ROW@North02.jpg

(119k) |

|

ClarkJct01.jpg

(136k) |

|

ClarkJct02.jpg

(201k) |

|

ROW@WillowPortal01.jpg

(180k) |

|

ROW@Ohio01.jpg

(187k) |

|

ROW@Ogden01.jpg

(150k) |

|

ROW@Hubbard01.jpg

(188k) |

|

ROW@Halsted01.jpg

(161k) |

|

ROW@Halsted02.jpg

(150k) |

|

ROW@Wrightwood01.jpg

(144k) |

|

ROW@Montana01.jpg

(222k) |

|

ctaS-718.jpg

(167k) |

|

ROW@Barry01.jpg

(222k) |

|

cta3200s@WellsBridge01.jpg (187k) A Kimball-bound Brown Line train of 3200-series cars crosses the Wells Street Bridge over the Chicago River, passing by a picturesque view of the river and skyline to the west in 2009. In the background is The Residences at RiverBend, a high-rise development on Canal Street on the west side of the fork in the Chicago River, built in 2001-02. On the right is River North Point (formerly 350 West Mart Center and originally the Apparel Center), located at the apex of the fork in the river known as Wolf Point, built in 1976 and now housing the Chicago Sun-Times newspaper as evidenced by the sign on the exterior. (Photo by Dennis Herbuth) |

|

cta5187.jpg (252k) |

|

ROW@Wacker-NewBridge01.jpg

(149k) |

|

ROW@Wacker-NewBridge02.jpg

(181k) |

|

ROW@Wacker-NewBridge03.jpg

(144k) |

|

ROW@Wacker-NewBridge04.jpg

(127k) |

|

ROW@Wacker-NewBridge05.jpg

(98k) |

|

ROW@Wacker-NewBridge06.jpg

(104k) |

|

ROW@Wacker-NewBridge07.jpg (185k) |

|

cta7005_5299_5615_20211104.jpg (226k) |

|

cta7005_20211104.jpg (207k) |

|

cta7003_20211104a.jpg (202k) |

|

cta7003_20211104b.jpg (217k) |

|

1. .

Gerasole, Vince. "Wood Already Rotting At New CTA Brown Line Platforms." chicago.cbslocal.com, August 29, 2011. Accessed December 12, 2012.

2. "Cost To Repair Brown Line Rehab Mistakes Swells To $5.7M." chicago.cbslocal.com, December 11, 2012. Accessed December 12, 2012.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.